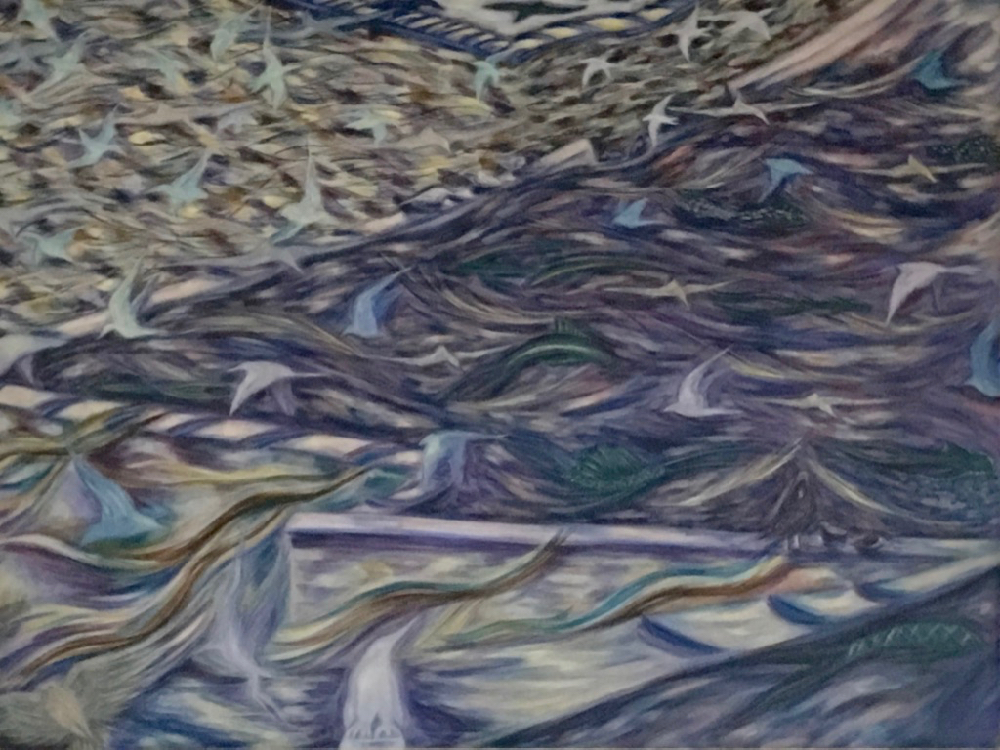

Flicker ©️2021 LSAuth. Oil, conte, gouache on rag paper.

We have art in order not to die of the truth.

—Friedrich Nietzsche

I spent a large part of my childhood discovering the outdoors, trying to save the animals, including insects, from premature death. Every summer the ants would resolutely march in and out of their hole-hills burrowed in the interstices of our sidewalk. I would examine their minute movements along their chain gang thread and marvel at how hard they worked. How could my brothers drop water balloons on their homes? I tried to thwart their efforts by constructing roofs over the openings, made of twigs and grass. My passionate yet naive efforts could not prevent the cataclysmic destruction —and so the ants’ colonies were doomed.

My crusades expanded when I was old enough to explore beyond my yard boundaries. Most of the time, all of the kids in my neighbourhood played together rather peacefully. But kids can be occasionally cruel. Various atrocities including pulling legs off of spiders, pinching wings off of butterflies, extracting lit abdomens from fireflies, to name a few, would bring out the warrior in me. I knew that I could not save the victims in their hands, but I could scream at the bullies and withhold future friendship if they continued in these barbarous acts. Some of us kids would have funerals for the unfortunate creatures and bury them along the creek bank. Insects, frogs, birds, drowned puppies & kittens, were some of the many to whom we solemnly and tearfully said goodbye as we sent them back into the earth, housed in a cardboard coffin with dandelions on top.

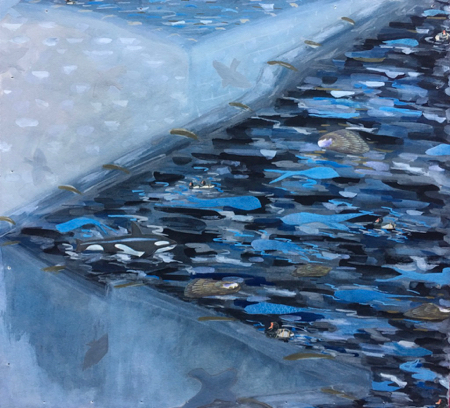

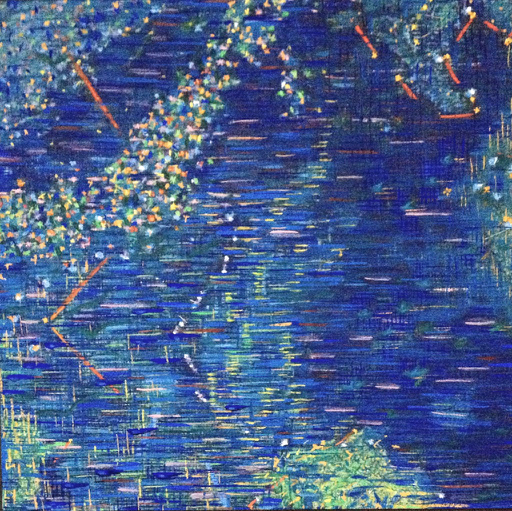

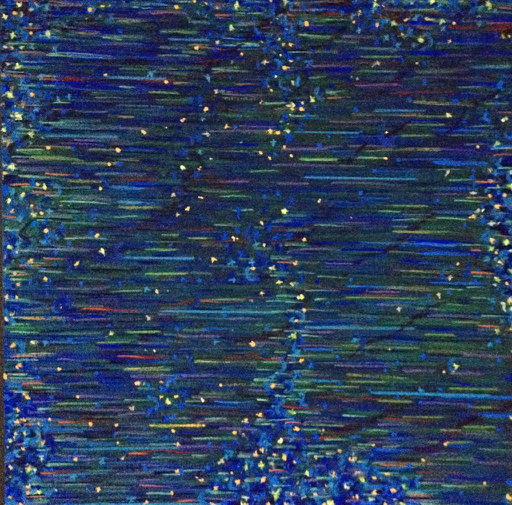

These drawings and paintings from My Fallen Birds continue my ritual of bearing witness to the brevity of a life. These birds are found on my walks, often on sidewalks and driveways, which I promptly document with a sketch and photograph for a later studio painting. I place them on an imaginary “map” to bring them out and beyond their local resting place.

These birds are not dead by a child’s hand, but rather by a domestic cat let outside by its owner — or a crash into some glass window. There is something about the absolute stillness of a creature that is normally in constant movement that always deeply affects me. As a youth, I never cared for the still life paintings in major museum collections with dead birds, rabbits, and other animals. With the exception of admiring the technical mastery, I didn’t feel the emotional thrust of what the paintings were saying about our own human mortality. Perhaps, I was too young.

I reflect on how childhood cruelties and adult indifferences have similar consequences on how they affect the life around us. Although I give to bird conservancy organisations, and I do not own a cat, and I try to prevent window collisions with films and decals, I am not an animal activist in any public way. I was more of one as a child, than I am today as a 60+ adult. Why this is, I am not sure, except I’m uncomfortable with anything that smacks of virtue signalling. I know that I am guilty of having done harm in my own life with my actions. Cruelty and thoughtlessness can be perceived as one and the same to the recipient of those actions.

In the end, I don’t know why I want to paint these birds. I just know that I need to. I am not making a particular statement. I am merely trying to live fully by observing my surroundings. Maybe it is my form of a prayer, an offering to the great unknown.

Above left to right: Hummingbird, Final Flight(Starling), and Robin.