… And he never had the sense of home so much as when he felt that he was going there. It was only when he got there that his homelessness began.”

―Thomas Wolfe, You Can Never Go Home Again

“The only journey is the one within.”

― Rainer Maria Rilke

I lived across the street from the Gothic architecture of Princeton University, which was very beautiful & serene but I also needed my gritty urban fix to create enough of an opposing force out of which to create. The train station was a short walk down the street from our apartment and I would try to visit New York once a week, spending a full day in the SoHo and Village art galleries. I would always end my day at Pearl Paint in Chinatown and savor every minute while there, studying the organized chaos of new stock items, breathing in the turpentine, and talking to the employees who were always some brand of artist. I still miss the informative social interaction that kind of store provided, which was so much more gratifying than the gallery scene.

Pearl Paint on Canal in Chinatown around 1985 NYC.

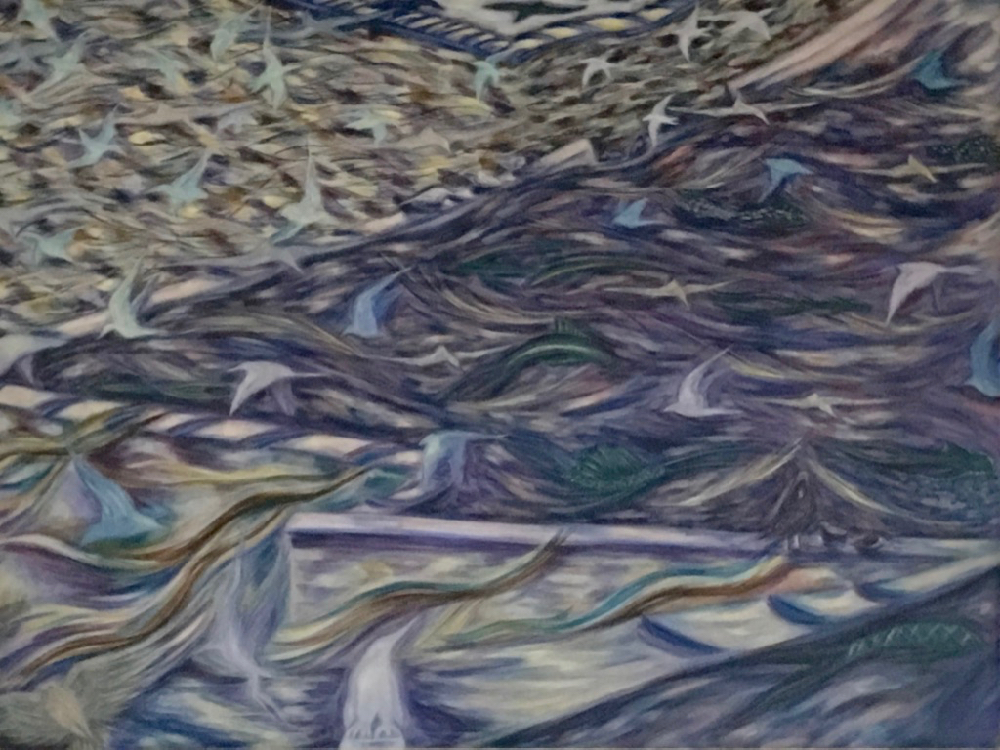

I walked everywhere in NYC and felt at home there as much as I did in the woods of Princeton. But I think I loved the train ride between the two destinations the most. It was always dark when I headed home, just like in Chicago times, and my legs & feet were tired. I saw & learned so much in one day. The amount of visual stimulation in NYC was always overwhelming and I would jot down my reflections in my sketchbook-journal on the way home. Everything seemed possible when I was moving, and I always equated train rides with hopefulness and freedom. I must have realized (didn’t I?) that those feelings were an illusion, that train rides were more of an escape from reality — the reality that no one really cared about art but the artist who made it. I always had a mini-emotional let-down the day after these trips because it was always clear to me that there was so much good work hanging in unpeopled rooms, unnoticed, unappreciated, and unloved. Why did the world need another artist?

But then I would get back into my studio the next day, with my new brush or tube of paint, and focus in on the pieces I had to finish and the new ones I had to start.

The Princeton “Dinky” around 1985.

On October 29th, 1985, after 17 months of living in Princeton, I went back to Chicago to exhibit my mixed media figures. Concurrent with this show was a 6-week "workation" as a resident artist at Ragdale Foundation in Lake Forest, Illinois — 30 miles north of Chicago. Michael & I loaded up a roomy & reliable one-way rental car with my carefully packed works, art supplies, and clothing, and drove for 2 days to Chicago. When we unloaded my work at the gallery, I felt like a visitor rather than a returning native. I missed Michael already as I left him at the airport for his flight back to Princeton. I returned the rental car and hopped on a train to Lake Forest. Through the window I watched the city buildings quickly metamorphose into trees. My new surroundings looked more like Princeton than Chicago and I walked the short distance from the train stop to Ragdale, eager to meet my fellow residents and share my first dinner with them.

This was to be my home for the next 6 weeks.

Portal to the Ragdale grounds

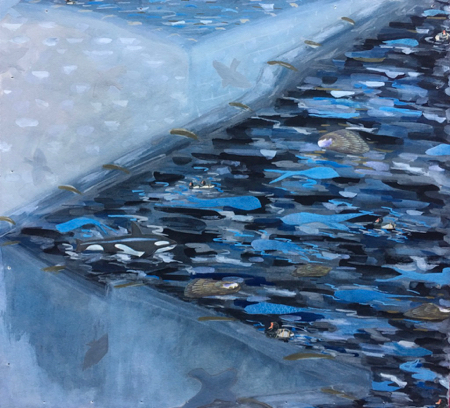

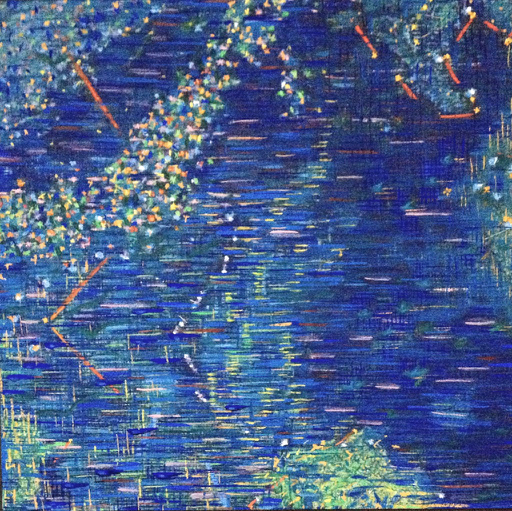

Ragdale was such a gift at the right time in my life. It provided a beautiful setting of woods and autumn foliage for my self-imposed limbo. After drawing all day in the studio, I would leave the grounds in the late afternoon for a quotidian walk to Lake Michigan. It occurred to me that my life was not all that different than the Princeton one that I had temporarily left behind. The primary difference was that I did not feel as solitary because almost everyone at Ragdale was an artist — even many of the staff and maintenance people. This collective connection was comforting to live around. We shared an enormous respect for each other’s needs of time & space. At night we all came together to sit at a very long dining table for supper and conversation. We talked about everything — except our work. Often it was the only time I spoke to anyone for over 12 hours. It was a true break from our inner demons and we laughed easily. After dinner many of us would go back to our private studios for a few hours and then meet back around the fireplace to listen to readings by the resident writers of their works in progress before going to bed.

Ragdale quarters.

Several of the residents came to my Chicago show which opened a couple weeks after I arrived in Ragdale. The reception was very festive and my co-exhibitor, Alex, & I were elated to have such a large crowd and enthusiastic response to our work.

Night of the Chicago opening November1985.

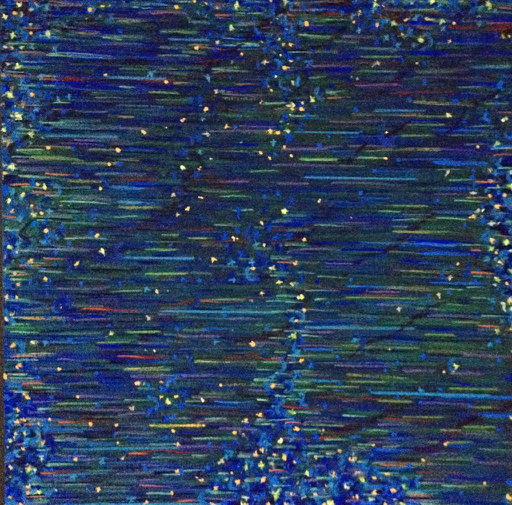

( Below are some of my works included in this show: Barabbas, Vesta, Cornstalker, and StarGazer. ) .

Of course, there was the late night train ride back to Lake Forest, and then the letdown the morning after the show. I learned that if a body of work that took several years to create gets you a party and an audience for 3 hours, then that may be as good as it gets in terms of recognition. I was back in my studio the next morning, facing lots of virgin white paper tacked onto the walls.

I am grateful to Ragdale and the people I met there. This particular residency provided me with the security of belonging to a community which I thought I needed at that time, to tacitly affirm that I was real. When I moved away from Chicago, I had not been confident that I could create totally on my own, every day, away from a particular locale, and away from other artists. I had not realized that I had already developed beyond that fear. Ironically, going to Ragdale brought me farther away from Chicago and closer to Princeton and other towns I would live in subsequently. Everything I needed was within all the layers of myself — not in a geographical location.

I had been making a life as an artist all my life. That is what I realized at Ragdale.

In The Wake Of Clouds ©1985-6 LSAuth. oil/linen